Gainesville, FL (PRWeb) February 16, 2023

Although the eminent domain power is an attribute of the sovereign, there are instances in which a private licensee is delegated the power for the acquisition of easements necessary to establish a lineal utility corridor. Congress, for instance, has authorized private licensee companies to use the power for natural gas pipelines under the Natural Gas Act (“NGA”).

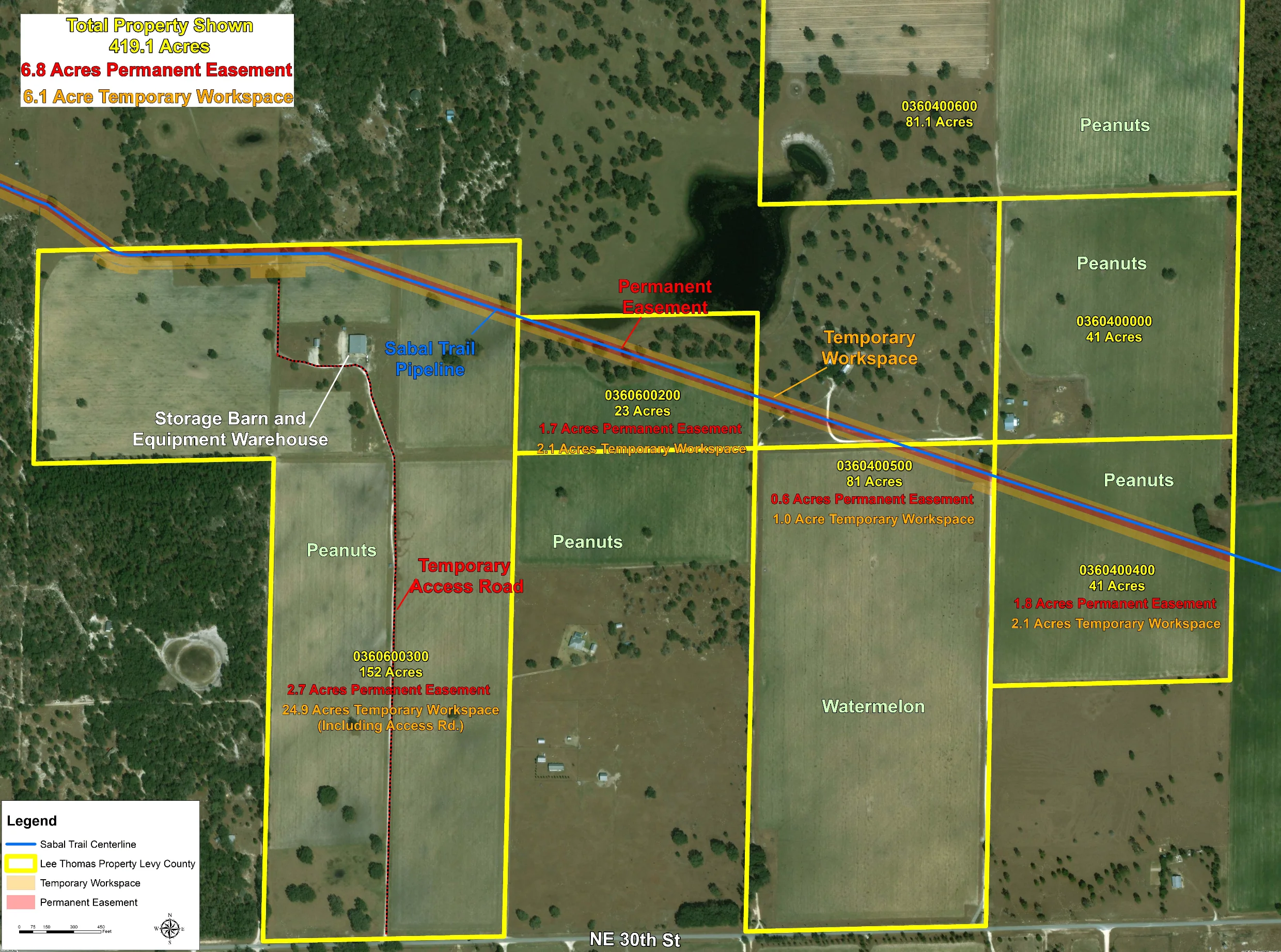

Enbridge-owned, Sabal Trail Transmission, LLC, (“Sabal Trail”), is a private licensee company that under the NGA exercised eminent domain to construct a 500-plus mile, 36-diameter, interstate pipeline transmitting 1 billion cu. ft. of gas per day to fuel electrical plants owned by Florida Power & Light and Duke Energy in Florida. Lee and Ryan Thomas were among Florida landowners in Levy County who had to litigate with the pipeline company over the measure of compensation for the taking of both permanent and temporary easements which diagonally crossed-through their lands comprising an 837-acre farm with an adjacent 40-acre homestead. As with other private licensee companies, Sabal Trail’s practice has been to offer owners only nominal compensation. Sabal Trail’s initial offer was $59,700 to Lee for the easements running through the 837-acre farm and $6,800 to Ryan for the easements running through his 40-acre homestead. While paying for the easements, the pipeline company contended that there were no severance damage to the owner’s remaining land because the pipeline was buried underground. Following two years of litigation, however, a jury awarded $861,264 to Lee and $463,439 to Ryan finding substantial damages.

Sabal Trail initially appealed these jury verdicts arguing that the district court erred by allowing Lee and Ryan to testify as to their own opinions of damages resulting from the easement takings for gas pipelines. The Eleventh Circuit denied this appeal and affirmed the right of owners to testify at trial regarding the measure of compensation for the taking of their property. See Sabal Trail Transmission v. 18.27 Acres of Land, 824 Fed. Appx. 621 (11th Cir. 2020). Sabal Trail then appealed the district court’s order below that required Sabal Trail to pay for the attorneys’ fees and costs that Lee and Ryan incurred because they are included in Florida’s state measure known as “full compensation.”

On February 3, 2023, the Eleventh Circuit held in favor of landowners, Lee and Ryan Thomas, that a private licensee company exercising eminent domain under the Natural Gas Act, must pay the measure of compensation established by state, not federal, law. Florida’s constitutional measure of “full compensation” requires a condemning authority to pay for the owners’ attorneys’ fees and costs in an eminent domain case. Federal law’s measure of “just compensation” does not. Following prior-precedent, the Eleventh Circuit expressly followed principles of federalism wherein state law delineating private property rights should not be displaced in favor of federal law unless its application would otherwise thwart a federal interest or program. Accordingly, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court below requiring that the private licensee company, Sabal Trail Transmission, LLC, pay for the attorneys’ fees and costs incurred by the Thomases to defend their property rights in the eminent domain proceedings for the taking of natural gas pipeline easements. Andrew Prince Brigham, Brigham Property Rights Law Firm, Mark F. (Thor) Hearne, II, True North Law Group, who served as the principal lawyers for the Thomas family, are available as sources for this press release.

Florida is one of a handful of states that includes attorneys’ fees and costs as part of an eminent domain award. Sabal Trail argued that it should be accorded the same regard as the federal government when it exercises the eminent domain power under the federal measure known as “just compensation” which does not require a condemning authority to pay for the attorneys’ fees and costs incurred by the owner.

Two weeks ago, on February 3, 2023, a three-judge panel of the Eleventh Circuit (Judges Rosenbaum, Jordan, and Steele) rejected Sabal Trail’s argument for a number of reasons. The two most important were that Sabal Trail’s argument violated the “prior-precedent rule” and Sabal Trail’s argument was contrary to constitutional principles of federalism.

The prior-precedent rule requires a three-judge panel of a federal circuit court to follow the decision of any previous panel of the circuit and, especially, any decision of the circuit sitting en banc. Federalism provides that state law, not federal law, defines the nature and extent of an owner’s interest in property. Florida’s state law provides that a property owner’s substantive rights to his or her property include the right of the owner to be reimbursed the attorney fees and costs the owner incurs when a condemning authority takes an owner’s property and forces that owner into court through no fault of his or her own. Over thirty-years ago, the Eleventh Circuit’s predecessor, the former Fifth Circuit, assembled en banc to consider exactly this issue in Georgia Power Company v. Sanders, 617 F.2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1980) (en banc). There, the Fifth Circuit held that state law defined the compensation an owner was due when a utility company took property under eminent domain authority the federal government granted electrical power companies under the Federal Power Act (“FPA”). Applying the same reasoning to the NGA, the Third Circuit and the Sixth Circuit followed Georgia Power in Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co., LLC v. Permanent Easement for 7.053 Acres, 931 F.3d 237 (3d Cir. 2019), and Columbia Gas Transmission Corp. v. Exclusive Nat. Gas Storage Easement 6, 961 F.2d 1192 (6th Cir. 1992). These decisions all followed and applied the Supreme Court’s Erie Doctrine and the Court’s decision in United States v. Kimbell Foods, Inc., 440 U.S. 715 (1979). Yet, despite the weight of this controlling-precedent, Sabal Trail sought to relitigate this settled rule of law in its appeal. The Eleventh Circuit panel issued its decision the day after Groundhog Day. This coincidence was not lost on the panel. The panel quoted their colleague, Judge Ed Carne’s decision in Atl. Sounding Board Co. v. Townsend, 496 F.3d 1282 (11th Cir. 2007), explaining, “Without the [prior-precedent] rule every sitting of this court would be a series of do-overs, the judicial equivalent of the movie ‘Groundhog Day.’ While endlessly recurring fresh starts is an entertaining premise for a romantic comedy, it would not be a good way to run a multi-member court that sits in panels.” Applying the prior-precedent rule, the panel held, “We therefore put Punxsutawney Phil aside and adhere to the prior-precedent rule.” Slip op. at 15.

The second reason the panel denied Sabal Trail’s appeal is that Sabal Trail’s argument was contrary to foundational principles of federalism, including the principle that state law (not federal law) defines private property interests and that the federal government may only displace state law when it is necessary to achieve a substantial and constitutionally legitimate federal interest. Judge Rosenbaum wrote, “[b]asic considerations of federalism” should provide the rules by which property is defined and compensation is determined. Slip op. at 18. Quoting Georgia Power, the panel held, “the premise [is] that state law should supply the federal rule.” And, where they may be a doubt, “we start[] with a presumption of sorts: that a tie would go to state law.” Slip op. at 18.

For these reasons, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision to award the attorneys’ fees and costs incurred by Lee and Ryan as part of the compensation that Sabal Trail must pay in accordance with Florida’s state measure of “full compensation.”

By way of editorial comment, the Thomases’ legal advocates, Andrew Brigham and Thor Hearne, pose this question: “Why is Sabal Trail and other private companies litigating against landowners so ferociously and, even more so, why are these companies willing to incur attorneys’ fees and costs that far exceed the amount the owners would have likely accepted if the company had offered to pay a fair price for the property it took up front?” Additionally, they ask, “Why was Sabal Trail appealing its obligation to pay the attorneys’ fees and cost incurred by the owners in this case when, for at least thirty years, the law on this point has been established and settled?”

Remarking with a bit of truthful sarcasm, these lawyers quip that, “Maybe it’s because these private, multi-billion, for-profit energy companies have money to burn.” With a more measured response, these lawyers add: “Unlike a governmental entity, that has some obligation to the society at large or accountability to the electorate, once its pipeline is constructed and operational, these energy companies can readily afford to low-ball offers, put a case on slow-burn, and leave the private owner to fight for years in court in order to be fairly compensated.”

Justice John Paul Stevens perceived and understood the situation some time ago. He answered these questions somewhat differently. “I reject [the Court’s] apparent unawareness of the function of the independent lawyer as a guardian of our freedom. That function was, however, well understood by Jack Cade and his followers, characters who are often forgotten and whose most famous line is often misunderstood. Dick’s statement (“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers”) was spoken by a rebel, not a friend of liberty. See W. Shakespeare, King Henry VI, pt. II, Act IV, scene 2, line 72. As a careful reading of that text will reveal, Shakespeare insightfully realized that disposing of lawyers is a step in the direction of a totalitarian form of government.” Walters v. Nat’l Ass’n of Radiation Survivors, 473 U.S. 305, 371 (1985) (Stevens, J., dissenting).

Yet, there continue to be some, even many, who want to get rid of lawyers. Nevertheless, here is a clear example where if lawyers were not brought in to defend private property rights and challenge the pipeline company, only nominal compensation would have been paid. Moreover, the virtues which undergird the principles of stare decisis, prior-precedent, and federalism would have gone unheralded. In the final analysis, if desiring meaningful protection of private property rights, reform should look to those instances where the measure of compensation includes having the condemning authority pay for the attorneys’ fees and costs incurred by the owner who has been so greatly put at risk by eminent domain.